“I just liked the matchup.”

Aaron Boone, NY Yankees Manager, explaining why he chose reliever Nestor Cortes, who had not pitched in 37 days, to face the heart of the LA Dodger lineup in the first game of the 2024 World Series with two runners on base, bottom of the tenth inning, and the Yankees sporting a 3-2 lead. Although he retired superstar Shohei Ohtani on one pitch and walked Mookie Betts to load the bases, Cortes’ first pitch to Freddie Freeman, the World Series MVP, got blasted over the right field fence for the first ever walk-off grand slam home run in a World Series. Propelled by that win, the Dodgers went on to win the Series four games to one.

O

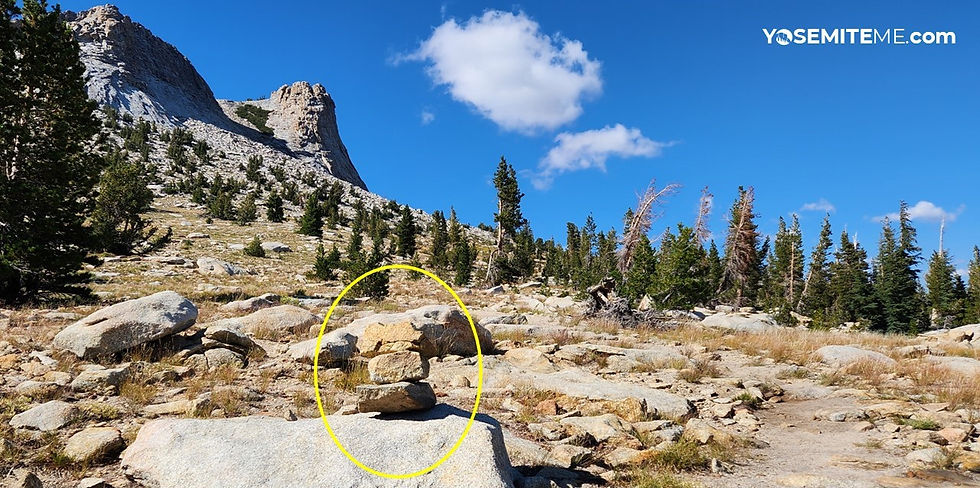

I arrived at the May Lake High Sierra Camp on Thursday, August 23 at 1:30 pm. I checked in and relinquished the burden of my backpack in preparation to climb Mt. Hoffmann. I could have waited until the next day to make the climb, but, like many of the choices we make, my decision to scale Hoffmann on the afternoon of my arrival had been influenced by my inability to rid myself of the memory of my failed attempt to climb the 10,843-foot (3,309 m) peak. A few years ago, a friend and I got shut out when a freak summer storm barraged us with a deluge of rain, snow, and ice, forcing us to abandon our trek to Hoffmann’s top (click here to read the story). Hoffmann easily triumphed over us on that stormy day.

Strangely, meteorologists were again forecasting a rare Alaskan cold front to come swooping down toward the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range, which Hoffmann calls its home base. The storm was projected to reach the Park late the following day, Friday. Not desiring to face defeat at the hands of another rogue summer storm, I decided to do the hike while blue skies prevailed.

I peered up at Hoffmann from the banks of May Lake. With the sun shining brightly, I thought to myself, I like the matchup. Sure, it had been five months since I suffered a contused lung, broke four ribs and four vertebrae, and received a huge gash in the back of my head (requiring staples) after falling off the roof of my home, but I had healed to about 95%. Regarding my physical conditioning, I had been exercising sufficiently to increase my lung capacity. I knew every breath would count as I scaled Hoffmann’s elevated summit.

Before arriving at May Lake, I had also spent three days in Yosemite Valley. Although its elevation averages about 4,000 feet (1,219 m), I believed that staying there afforded me time to acclimate my lungs to the higher elevation.

I started the 1 ¾-mile journey (2.3 km) to Hoffmann at about 2 p.m., knowing that I needed to be back by 6 p.m. for dinner at Camp. I moved quickly over the forested part of the hike and the first rock field. More trees ensued and I struggled up a bushy incline while trying to follow a semblance of a trail. Moving out of the bushes brought me to a grinding hike up another rock field where the trail disappears due to the vast slabs of granite. Rock cairns placed hither and thither proved fairly accurate and guided me much of the way. However, their guidance extended the time to traverse this part of the trail due to the guessing game required to discern their message.

Periodically, I exchanged trail positions with a group of seven younger hikers. I passed them when they rested and they passed me when I rested. We used each other as guides to calibrate our trail-finding skills. I urged them on and they did the same to me.

Once I reached the open rock field that exposed the summit of Hoffmann, the trail became abundantly clear as many trekkers before me had compacted the gravelly surface. As the path ascended upward, my lungs began to labor. Rest breaks became more frequent. I clearly had overestimated the acclimation I thought I had procured while in Yosemite Valley. However, the 180-degree open vistas south and east of Hoffmann made stopping all the more rewarding. Half Dome, Cloud’s Rest, Tenaya Lake, and the Clark Range kept my eyes transfixed on the horizon as I made my way to the base of Hoffmann. Those views gave me excuses to stop, to maximize my lung intake, and to urge myself onward.

The group of seven and I reached the base of Hoffmann at about the same time. They

offered me snacks as they prepared to go the last leg up the craggy incline. On the right side of the ridge that dips to the base of Hoffmann and beyond the ice slab nestled in its shadow, I looked out westerly to the Ten Lakes wilderness area, about a thousand feet below where I stood.

The remaining 200 to 300 yards to the top of Hoffmann would require scrambling over piles of rock slabs angled on top of each other. Perhaps I should have rested longer like my seven co-hikers, but I decided to start the final scramble to the top of Hoffmann.

I ambled to the left and gained elevation while moving parallel to the ridge at the top. Finally, I angled toward the top and its radio tower, and scrambled upwards. My attention veered from the task at hand when I heard exuberant shouts from three hikers who had blown past me earlier on the trail. They stood about 100 yards above me on top of Hoffmann, ecstatic at their victory.

As for me, the thin air began to tax me. Getting back to Camp intact now became my sole concern. I understood that every scramble that lunged me forward, would have to be repeated on my way down. It did not take much rock climbing to convince me it would not be wise to continue.

Hence, I took one last look at the joyous victors near the radio tower, mumbled defeat to myself, and slowly retreated from my attempt to scale Hoffmann’s peak. I took some comfort in viewing the vast landscape spanning the horizon to the south and east of me as I began my descent from Hoffmann.

Halfway down one of the expansive rock fields, I spooked a marmot. It speedily motored away from me across the rocky granite landscape, assuring me that no autograph or signed paraphernalia from this twice-beaten competitor could entice it to hang out for even a moment.

Two sooty grouse emerged from a dugout in the rocks and underbrush. Their apparent disinterest in me seemed to signal that they too had seen this battle before, where the “visitors” come into Hoffmann’s home territory and go away humiliated. To make matters worse, their soft cooing sounded as if they were mocking me: “Yooou . . . yooou . . . loooser.”

Yes, I had liked the matchup for this second round of competition with Hoffmann. Yet, I struck out despite the decisions I made that I thought would lead me to victory. Hoffmann wins the best of three. I can see only one remedy for this loss: “Hey, Hoffman, how ‘bout we make it best of five?”

Image Below: On the banks of May Lake looking toward Mt. Hofmann.

Comments